Our project site for all things New England cottontail and young forest is now up and running! Learn more about our ongoing research with New England cottontails (aka the wood rabbit) and the young forests they, as well as many other species, rely on. You can read about our creative solutions to improve woodlands for imperiled species, the researchers working to make this happen, as well as explore different ways to get involved. Don't forget to browse some of our photos from the field!

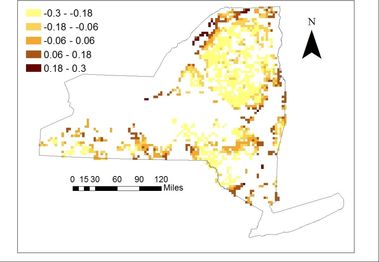

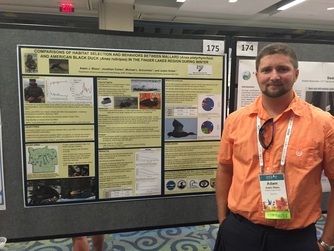

A New England cottontail rests on a log in a Hudson Valley forest. A New England cottontail rests on a log in a Hudson Valley forest. Many wildlife species live in patchy habitats. Animals move between patches frequently or not, but connectivity among patches is maintained and populations persist. Occasionally a bad year, disaster, or just bad luck wipes out all individuals in a patch but new individuals eventually find it, move in and the system remains stable. These systems are generally referred to as metapopulations and many species have existed in stable metapopulations for millions of years. However, today, the connections between the individual patches making up metapopulations are increasingly fragmented by roads, human development, or otherwise altered habitat. As a result, metapopulations may be fragmented into multiple, smaller parts and their individual patches may more frequently blink out and it may take longer for them to be recolonized-or they may never be recolonized. The end result is population declines as individual patches are lost but never recolonized leading to an increased susceptibility to permanent metapopulation extinction. Recent research led by Dr. Amanda Cheeseman of SUNY-ESF suggests that this scenario is occurring in even the most secure populations of New England cottontails raising concerns for the status and long term stability of populations in New York and across their range. Her work, recently published in Conservation Genetics builds off of a rich literature suggesting that populations of New England cottontails are highly susceptible to metapopulation breakdown as a result of habitat loss and poor connectivity among remnant populations. Her findings suggest that habitat loss and fragmentation by roads in New York have created a patchwork of unsustainably small populations, each displaying indicators of decreased genetic diversity. Restoring connectivity among fragmented metapopulations in an effort to increase population size to sustainable levels should be a priority for managers. A combination of habitat creation, a focus on creating wildlife corridors, and translocation and reintroduction efforts may be necessary to achieve these goals.  Michelle talks about waterbird research techniques with workshop participants at the Khijadiya Bird Sanctuary. Michelle talks about waterbird research techniques with workshop participants at the Khijadiya Bird Sanctuary. Dr. Cohen and Ph.D. students Michelle Stantial and Alison Kocek recently had the exciting opportunity to teach a one-week workshop on Coastal Waterbird Ecology Concepts and Techniques in Jamnagar, Gujarat State, India. The workshop was hosted by the Gujarat Ecological Education and Research Foundation (GEER), a program of the Gujarat Forest and Environment Department Department. In partnership with the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), we led a series  Alison (holding a whimbrel) and Michelle (holding a curlew) assist in the BNHS nighttime banding demonstrations. Alison (holding a whimbrel) and Michelle (holding a curlew) assist in the BNHS nighttime banding demonstrations. of lectures and field exercises focused on different aspect of coastal waterbird ecology. Gujarat is on the Arabian Sea along the west coast of India, and has the longest coastline of any state, as well as 28,071 square kilometers of coastal wetlands. As such, it hosts a tremendous diversity of waterbird species, including waterfowl, shorebirds, wading birds, and seabirds. On the first day of the workshop, we participated in a seminar attended by approximately 100 students, scientists, and members of the public. In addition to a talk by Dr. Cohen on global status and trends in waterbirds, there were speakers from across India that spoke about conservation of wildlife in India, including research programs, citizen science, and Indian law.  Alison records data for Tuhina Katti, a member of the BNHS bird-banding team. Alison records data for Tuhina Katti, a member of the BNHS bird-banding team. The workshop began the next day, with around 60 participants including undegraduate and graduate students from around Gujarat as well as members of the Gujarat Forest Department. Day 1 included lectures by Dr. Cohen and his students on conservation and research of beach-nesting birds, saltmarsh birds, and long-distance migrants, as well as the use of birds as biomonitors, followed by an introduction to statistical models in ecology. That set the stage for the remaining days, which focused  Alison and Michelle set up a whoosh trap demonstration on the sandflats of Balachadi. Alison and Michelle set up a whoosh trap demonstration on the sandflats of Balachadi. on survival, occupancy, and abundance modeling as well as behavioral and habitat selection studies. Each day also included field demonstrations led by BNHS, Alison, and Michelle. January is the nonbreeding season for waterbirds in India, and capturing birds requires traps set in foraging and roosting areas. We had the privilege of working alongside BNHS biologists as they captured birds with "mesh nets", a technique similar to mist nets, in their post-sunset trapping operations and applied leg bands and  Members of SUNY-ESF, GEER, and BNHS at Balachadi. Members of SUNY-ESF, GEER, and BNHS at Balachadi. individually-identifiable plastic flags. BNHS will use these flags to get recapture and resighting information from other sites within the Central Asian Flyway, and to thus learn about migratory connectivity of their wintering sites with breeding sites in Europe and Asia. Michelle and Alison demonstrated their capture techniques during daylight hours, including "whoosh nets" (a bungee-propelled projectile net) and drop nets. Leading the workshop was the experience of a lifetime, and ended with the potential for many future collaborations with our new friends and colleagues!  Melissa Althouse scans a flock of common terns and roseate terns Melissa Althouse scans a flock of common terns and roseate terns Bird migration is one of the most spectacular phenomena in the animal kingdom, with some species traversing the distance from the Arctic to the Antarctic and back each year. Such a journey is energetically costly and physically demanding, and successful migration requires that birds be the best possible condition at the outset. High quality staging grounds (where some species flock up after the breeding season is over prior to migrating) and stopover areas (where some species flock up in the midst of a migratory journey to refuel) are essential for the survival of migration. Eastern Canada and the northeastern United States are home to an endangered population of roseate terns, which nest in mixed-species colonies on coastal islands and stage with their offspring primarily along Cape Cod, Massachusetts prior to migrating to the Carribean and South America directly over the Atlantic Ocean. Adult roseate terns catch small fish by plunging into the sea, and continue to bring food to their young during the staging period. At that time of year, they require quiet, undisturbed mudflats and beaches , where they can relocate their young and spend time resting and saving energy for the long journey to come. From late July through August, however, their preferred staging site at Cape Cod National Seashore is also one of the most popular destinations in the world for human beach recreation, leading to the continual potential for disturbance of roosting flocks that threatens their ability to store up the necessary energy for migration. A new paper in the Journal of Wildlife Management by Melissa Althouse reports the results of a human disturbance study to mixed-species flocks of common terns and roseate terns during the post-breeding staging period at Cape Cod, funded by the National Park Service. Melissa and her crew observed the interactions between tern flocks, human pedestrians, and other potential disturbance sources such as gulls, which steal fish from terns returning to their roosting areas, and shorebirds which are not a threat but do produce alarm calls that can rouse tern flocks. She recorded the distances at which approaching disturbance sources caused flocks to flush into the air, which uses up much-needed energy. Melissa found that human beachgoers at a distance of 100 meters from tern flocks led to about 4% of the flock flushing, which was about the same response observed to shorebird alarm calls when no humans were nearby. She also found that smaller tern flocks were more sensitive to human presence than large flocks. Based on these findings, managers can use signs and fencing to give terns space from human disturbance, during this critical time of year for energy conservation.  A New England cottontail ventures into the open. A New England cottontail ventures into the open. Prior to the 1900's, only one species of cottontail rabbit inhabited the northeastern United States to the east of the Hudson River. The New England cottontail, which relies on dense shrubby understory characteristic of younger stages of forest regeneration, had a range that spanned from the Hudson Valley in New York to Cape Cod in the east and Maine in the north. Over the latter half of the twentieth century, its habitat became increasingly rare as rural areas were abandoned by humans, shrublands gradually grew into mature forest, and other shrublands were lost to human development. As a result, New England cottontail populations plummeted. As habitat loss and population declines were occurring, a closely-related rabbit species, the eastern cottontail, which was introduced by the thousands into New England for recreational hunting began spreading and establishing itself in the wild across eastern New York and southern New England. The eastern cottontail likes young forest but, unlike its native cousin, also is comfortable in open fields and residential yards. Conservationists have long been concerned that eastern cottontails might be able to outcompete New England cottontails for habitat in young shrublands, worsening the population decline of the latter and making habitat restoration for New England cottontails more complicated. A new study led by Dr. Amanda Cheeseman and recently published in Ecology and Evolution confirmed that there is cause for concern about competition between the two cottontail species. Her results demonstrated that where eastern cottontails were prevalent, New England cottontails tended to choose sites with traits representative of mid- to late stages of forest succession such as dense tree canopy cover, tall shrubs, and moderate densities of Japanese barberry, an invasive understory shrub that thrives in low sunlight conditions. Where eastern cottontails were not prevalent, New England cottontails tended to choose sites with low to moderate tree canopy cover and areas of higher grass and herbaceous cover, characteristics common of earlier stages of forest succession. The displacement of New England cottontails into later successional forest by eastern cottontails could impact the survival and population trends of the native rabbit, a subject of ongoing study by the Cohen lab. The findings also have important implications for habitat restoration to benefit the New England cottontail, which until now has focused strongly on completely removing tree canopy cover to allow growth of shrubs and herbaceous vegetation. With eastern cottontails common throughout most of the range of New England cottontails, such an approach could encourage the competing eastern cottontail, which thrives in open areas, while having minimal benefit to New England cottontail. Experimental management that preserves different levels of tree canopy and understory shrub cover in areas that vary in eastern cottontail prevalence is underway in New York. We hope that with new information, we can help managers to reverse the decline of this unique part of our natural heritage.  Snowy plover on the road's edge at Gulf Islands National Seashore, Florida Snowy plover on the road's edge at Gulf Islands National Seashore, Florida Wildlife road mortality is a highly challenging issue for conservation, because roads are ubiquitous and the threat of vehicle strikes may not be factored into animals' habitat selection decisions. As such, roads may turn otherwise attractive habitat into ecological traps, where survival or reproduction are below levels that a local population needs to be sustainable. Estimating the numbers of animals killed by vehicle strikes in a locale is not as straightforward as it seems, because carcasses may disappear from roadways due to scavenging and decomposition faster than observers can count them. Additionally, observers may miss carcasses during surveys. Both problem lead to counts that are biased below true abundance. Statistical models to estimate abundance that rely on marking carcasses so that persistence rates and detection rates can be corrected for have been developed. They have traditionally relied on having at least 2 cooperating observers, one that initially marks the carcasses, and another that tries to relocate marked carcasses so that detection rate can be determined. In some instances, resource availability may limit the number of personnel available for carcass surveys. A new paper in the Journal of Wildlife Management authored by Maureen Durkin details a new method for estimating carcass abundance in the road when only a single observer is available, that relies on conducting two transects per survey day in close succession. Maureen's research focused on wildlife mortality at Gulf Islands National Seashore in Florida, where a paved road runs throughout habitat used by a variety of species including nesting shorebirds and seabirds. Her work demonstrated that all manner of taxa were affected by road mortality, including the Snowy Plover, a shorebird that is considered threatened in the state. She also showed conclusively that opportunistic road surveys miss large proportions of carcasses, and will serve to help make road mortality surveys more efficient and effective.  Justin Droke successfully defended his Masters Thesis, "Comparison of Spring Migration Ecology of Black Ducks and Mallards in the Montezuma Wetlands Complex". Declines in black duck populations in the twentieth century in conjunction with a dramatic expansion of mallards into the historic black duck range have raised concerns about the effect of competition between these two species on the black duck. Although mallards have been shown to displace black ducks in some breeding areas, there has not been any research until now on interactions between them during spring staging. Staging is a critical time of year for energy acquisition, as migratory waterfowl gather in productive habitat to build fat reserves for their long journey. Factors that disrupt the acquisition of food during staging can delay departure dates thus allowing competitors to settle in prime breeding habitat first, can lower the rate of survival during migration, and can lead to poor body condition upon arrival in breeding areas thereby affecting reproductive success. Competition for food with the closely-related mallard has the potential to affect nutrient acquisition by black ducks. Justin found evidence of habitat separation between mallards and black ducks at Montezuma, a site of very high importance to migrating waterfowl in the Atlantic Flyway. His results will inform management of wetland complexes to benefit black ducks in the presence of their closest competitor. Well done on an excellent thesis defense!  From left: Justin Droke, Sam Mello, Amanda Cheeseman, Alison Kocek, Jonathan Cohen, Adam Bleau From left: Justin Droke, Sam Mello, Amanda Cheeseman, Alison Kocek, Jonathan Cohen, Adam Bleau Braving an early spring blast of ice and snow, members of the Cohen Lab traveled to Burlington, VT this week to present their work at the Northeast Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies annual conference. On our first afternoon, post-doc Amanda Cheeseman co-moderated a symposium on current scientific knowns and unknowns in the ecology and conservation of the New England cottontail, which she organized with our collaborator Dr. Adrienne Kovach of the University of New Hampshire. The New England cottontail is a critically imperiled rabbit native to the northeastern U.S. that faces numerous threats discussed by the symposium speakers. Dr. Kovach began by summarizing our current knowledge on the species population structure, and Amanda presented her Ph.D. work on habitat selection and competition with non-native eastern cottontails. Samantha Mello spoke about her Master's work on parasites of the two species, and other talks focused on captive breeding and release efforts, rangewide disease and parasite studies, population viability and response to management, and the multi-state collaborative monitoring effort for the species. The symposium represented the first time that researchers from all the Universities studying the New England cottontail organized a scientific meeting to synthesize their work, including SUNY-ESF, the University of New Hampshire, the University of Rhode Island, Brown University, and the University of Connecticut. In a concurrent session that afternoon, Dr. Cohen presented the work of Ph.D. student Michelle Stantial on the application of miniaturized GPS tags for tracking piping plovers during the breeding season. Michelle has demonstrated that high-resolution habitat use information for this threatened species can safely be obtained using these 1-gram transmitters. The Cohen lab's bird projects took the stage for the second day of the conference, beginning with Justin Droke's presentation of his Master's work on spring staging interaction between American black ducks and mallards, followed by Adam Bleau's parallel work on competition between these two species in the winter. Black ducks, native to the northeastern U.S., saw sharp population declines in the 20th century, and the closely-related mallard expanded rapidly into their range. There have been several hypotheses to explain the black duck decline, and Justin and Adam's work focuses on the role of competition with mallards in the nonbreeding part of the annual cycle. Alison Kocek gave our final talk of the conference, unveiling her results on the use of PIT tags attached to legbands to greatly reduce capture and handling of birds in tidal marshes, while at the same time greatly increasing the rate of identification of individual nesting birds compared to repeat captures. Her work focuses on  The Cohen Lab is proud to announce that Adam Bleau has completed his thesis defense. Adam investigated the ecological interactions between American black ducks and mallards wintering in the Finger Lakes region of New York. The black duck is native to the eastern U.S. and declined drastically in the later 20th century. The more common mallard invaded the geographic range of the black duck, aided by land use changes and release of captive-bred birds to augment the population for hunting. Understanding the reason for the black duck decline, and the role of competition with mallards, has long been of interest to wildlife managers. Adam perform occupancy and behavioral surveys and tracked ducks with satellite tags for two winters to compare home range and habitat use between the two species. His work highlighted the differential response of black ducks and mallards to human development as well as the potential importance of remnant emergent marshes in the region. Adam did an impressive job navigating complicated field and analytical issues, and putting everything together for his thesis. Congratulations, Adam!  Samantha Mello has successfully defended her Master's Thesis, "The Parasite Diversity of New England Cottontails and their Habitat When Non-Native Species Are Present." Samantha studied ticks and Eimeria, a genus of protozoan endoparasite, in the imperiled New England cottontail and a non-native competitor, the eastern cottontail. The New England cottontail is the only native cottontail rabbit of eastern New York and New England, and has declined drastically due mainly to the loss of its early successional forest habitat. Parasites are a potential concern for the recovery of this species because they have been known to limit populations of mammals especially when they are small and isolated, as is the case for New England cottontails. Moreover, reintroduction of captive-bred rabbits to the wild as well as translocations among sites is part of the conservation strategy for the cottontail, which may inadvertently lead to the spread of parasites. Samantha demonstrated that the presence of invasive vegetation influences tick burdens on New England cottontails, which should be a consideration for both habitat restoration and translocation project. Congratulations to Sam for an excellent capstone to several years of hard work!  A trail camera deployed by Dr. Amanda Cheeseman catches a New England cottontail out in the open. A trail camera deployed by Dr. Amanda Cheeseman catches a New England cottontail out in the open. Created by nature’s most destructive forces, young forests teem with life. These ecosystems are home to hundreds of wildlife species, and are among the most diverse forests in the northeastern United States. However, human activity has led to a landscape where young forests are increasingly rare. Today, while our forests are aging, our young forests are disappearing. The losses of our diverse young forests and their abundant resources have contributed to the decline of many of the Northeast’s iconic species, such as New England cottontail. As part of a larger effort to restore habitat for young wildlife, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) has recently acquired Doodletown Wildlife Management Area, where they hope to create young forest within areas of the property, in part to create habitat for the New England cottontail. To inform local stakeholders and alleviate public concerns that have arisen over the initiative, the NYSDEC held a public town hall and invited experts to discuss the benefits of young forest to and forest management toward sequestrating carbon, improving bird populations, and recovering the New England cottontail. Dr. Amanda Cheeseman represented the ongoing work on New England cottontail and young forest management in the Cohen Lab, discussing the current state of New England cottontails in New York and the need for young forest to ensure the persistence of the species. In the end, while a few concerned citizens remain the public response for management of young forest was overwhelmingly positive. The workshop was featured on the front page of The Columbia Paper's online edition.  Participants in the 2017 Structured Decision Making workshop on predator control to benefit piping plovers. The workshop was held at Parker River National Wildlife Refuge. Participants in the 2017 Structured Decision Making workshop on predator control to benefit piping plovers. The workshop was held at Parker River National Wildlife Refuge. The decision to decrease a population of one species to benefit another is often one of the most difficult in wildlife management. Predator removal has become a common tool for improving reproductive success of the piping plover, a threatened shorebird on the Atlantic Coast of North America. However each decision to remove predators from an ecosystem faces biological, economic, and political uncertainties. Such uncertainties must be addressed if decision makers are going to gain confidence in their policies, which is especially important when a decision may be controversial. Structured Decision Making (SDM) creates a framework for rationally evaluating alternative courses of action, such that all stakeholders can see the values that go into a decision, discuss the weights they attach to those values, and predict the outcomes of alternatives. In October, the Cohen lab participated in an SDM workshop focused on predator removal to benefit piping plovers and least terns on the Atlantic Coast. Biologists and wildlife managers from Maine and Massachusetts worked with SDM coaches, including Dr. Cohen and Ph.D. student Michelle Stantial, to address predator removal decisions in their respective states and to learn from common problems. Biological uncertainty became a centerpiece of the discussion, and the workshop resulted in a decision by one state to try and reduce the scientific uncertainty with a study using retrospective data and a prospective study design. In addition, the coaches developed a decision tool for site selection for predator control based on the following stakeholder values, the weights placed on those values by the workshop participants, and currently available data: number of plover fledges produced, number of other plover nesting sites benefiting from predator removal at treatment sites, and number of sites with least terns that would benefit. Although several areas of uncertainty remained to be addressed after the one-week workshop, the workshop helped to bring order to highly complicated issue and follow-up work is planned in to further refine the decision making process. We arrived in force at the 24th annual meeting of The Wildlife Society in Albuquerque, NM in September. All in all, 9 members of the lab presented talks! These included an encore performance from former post-doc Abby Darrah discussing structured decision making for exclosure use to manage piping plovers, and a farewell performance from the recently graduated Michelle Peach who spoke about characteristics of forest bird species that affect the relationship between Breeding Bird Atlas block occupancy and protected lands. In their concurrent sessions, Michelle and Alison Kocek kicked off the conference with their opening talks, with Alison discussing the effects of nest fate on habitat selection by saltmarsh obligate sparrows. Also on opening day, Maureen Durkin described concerning results of her population projection models for snowy plovers in Florida and the role of road mortality at Gulf Islands National Seashore. On the second day of the conference, Adam Bleau presented a poster on interactions between wintering mallards and American black ducks in the Finger Lakes. In a stunning development, with the encouragement of his co-advisor Dr. Michael Schummer, Adam agreed to turn his poster into a presentation to take the place of a cancelled talk during the next day's waterfowl session. He managed to head to the Rio Grande to pick up his life roadrunner early the next morning and still do an excellent job with his talk explaining the strong positive influence of mallards on the distribution of black ducks and the negative influence of human development. Justin Droke then presented the sequel, with his results demonstrating differential habitat use by mallards and black ducks in the Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge during spring staging. On the final day of the conference, Samantha Mello spoke about parasites of the imperiled New England cottontail, which she showed hosted potentially detrimental levels of ticks as well as protozoan endoparasites sometimes associated with pathological effects in rabbits. Amanda Cheeseman gave her first talk as a post-doc, describing dispersal and exploratory movement rates of New England cottontails and their non-native competitor the eastern cottontail in New York, with her results implying that colonization of new patches is unlikely. Michelle Stantial gave the lab's final talk of the conference, with an occupancy model that showed foxes in piping plover habitat tend to stick to dune areas, providing some important insights for habitat restoration to reduce predation risk. Congrats to all my lab, I could not be more proud of the job you do at events like this and throughout your programs!  Members of the lab and recent alums present their research at The Wildlife Society's 24th Annual Conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico. From top to bottom and left to right, the presenters are: Michelle Peach, Alison Kocek, Abby Darrah, Maureen Durkin, Adam Bleau, Justin Droke, Samantha Mello, Amanda Cheeseman and Michelle Stantial. Bottom Right: The lab goes bird (and rabbit) watching at Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge.  Amanda comes to the conclusion of her defense seminar. Amanda comes to the conclusion of her defense seminar. This week Amanda Cheeseman successfully defended her Ph.D. dissertation, "Factors Limiting the Recovery of the New England cottontail in New York." Amanda's dissertation is the result of a three-year field project focused on the effects of competition and invasive species on a highly imperiled rabbit in New York. The New England cottontail, a shrubland obligate and the only native cottontail east of the Hudson River, is the focus of a six-state collaborative effort to restore habitat and recover populations. Amanda's results have clear implications for managing habitat to promote New England cottontails while discouraging their closest competitor, the eastern cottontail, which was introduced to the region. Her dissertation also highlights the importance of restoring connectivity within the New York metapopulation. Amanda has had a distinguished Ph.D. career. She has presented her findings around the world, and her work earned her a best poster award from the American Society of Mammalogists. She has been successful at grant writing, and is also often sought after when decisions are made about habitat management for New England cottontails. It was gratifying to see many members of the conservation community for the species attending her capstone seminar via webconference. The Cohen lab is extremely fortunate to have Amanda staying on for postdoctoral work, translating her Ph.D. findings into best management practices and adaptive management protocols and working with landowners on implementation of her recommendations. Congratulations, Amanda, and we're looking forward to continuing to work with you!  Michelle presents her capstone seminar Michelle presents her capstone seminar We are proud to congratulate Michelle Peach, coadvised by Dr. Cohen and Dr. Frair, for successfully defending her dissertation this week. Michelle's project is entitled "Evaluating The Roles of Protected Areas in Mitigating Species' Reponses to Climate and Land Use Change." For her dissertation, Michelle developed a new dynamic occupancy model for Breeding Bird Atlas data, and applied it to 97 species of birds in New York and Pennsylvania. She documented trends in block-level colonization and extinction based on species habitat preference and breeding range, among other factors. Michelle has had a very successful program at SUNY-ESF. She served as the primary instructor for our capstone Wildlife Major course, received a best paper award at the North American Ornithological Conference, and published one of her dissertation chapters in Journal of Applied Ecology. From here she will go on to a post-doc at University of Rhode Island. It has been wonderful working with Michelle and we wish her all the best!  Top: Michelle Stantial (left) and Alison Kocek (right) set up mist nets. Center: An American goldfinch at the Baltimore Woods MAPS station. Bottom: Alison Kocek talks about bird banding with visitors, as Dr. Cohen looks on. Top: Michelle Stantial (left) and Alison Kocek (right) set up mist nets. Center: An American goldfinch at the Baltimore Woods MAPS station. Bottom: Alison Kocek talks about bird banding with visitors, as Dr. Cohen looks on. The Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) program has been tracking continental trends in bird populations since 1989. Run by the Institute for Bird Populations, MAPS consists of a network of banding stations throughout the U.S. and Canada. Data collected from MAPS stations are crucial for understanding how habitat loss, climate change, and other large-scale factors affect the abundance and distribution of birds, and are used to inform policy and conservation actions. Onondaga Audubon Society (OAS) and SUNY-ESF's Department of Environmental and Forest Biology (EFB) have jointly re-established a MAPS station at Baltimore Woods Nature Center in Marcellus, NY that has been inactive since the early 1990's. The effort has been led by OAS President Alison Kocek and OAS Board Member Michelle Stantial, both of whom are Ph.D. candidates in the Cohen lab. On weekends throughout the summer, Alison and Michelle, with a team of volunteers that includes Dr. Cohen, work from sunrise to noon banding and taking measurements on birds at the Nature Center. They will report their data to MAPS, where it will be incorporated into statistical models of survival and reproductive success. In this way, we hope to understand how bird populations at Baltimore woods will change over time, and to contribute to scientists' understanding of how we might reverse declines that are currently observed for many of our avian species across North America.  Example of the estimated change in the occupancy probability of an avian species over time in New York Example of the estimated change in the occupancy probability of an avian species over time in New York Breeding bird atlases are unique datasets that rely on volunteers to collect information about where birds are found across entire states at a very fine scale. New York, for example, contains over 5,000 individual atlas blocks with a record of every species that was observed there in the early 1980s and again in the early 2000s. As a result, Atlas data can offer powerful insights into the factors that shape species distributions over time. One problem with Atlas data, however, is that they haven’t been collected in a way that makes it easy to account for imperfect detection. When a volunteer is out in the field looking for birds, inevitably a few species will be missed due to secretive behavior, misidentification, or even poor weather conditions. Failure to account for imperfect detection of birds that are actually present means we will underestimate how widespread those species are and potentially draw inaccurate conclusions about the factors that influence their distributions. Typically, researchers estimate detection probability by visiting the same site multiple times and recording how often each species is observed. Atlas data does not include information about how often a species was detected in each block. It does, however, include an estimate of effort, or the amount of time spent surveying. Ph.D. student Michelle Peach and coauthors have published a method in Journal of Applied Ecology to account for imperfect detection with Atlas data using effort as a surrogate for repeated surveys and covariates, such as habitat availability, to estimate whether a block was truly occupied or not. The approach was applied to model Canada warbler distributions in New York over a 20 year period and demonstrated a potential decline that wasn’t seen using other methods. It was also found that declines were particularly high in areas where Canada warblers were initially more likely to be found. This approach thus makes it possible to both identify declining species and more effectively target conservation efforts.  Amid fears about rollbacks to environmental protection and wildlife conservation, it can be difficult for scientists who want to make their voices heard to decide where and how best to focus their efforts. To that end, Ornithology Exchange is hosting an Ornithological Council (OC) database of pending congressional legislation that affects wildlife and other aspects of the environment. The site also contains an article explaining why filtering such legislation is necessary and providing protocols for approaching members of Congress. The Legislative Alerts Database contains an assessment of the urgency of a threat to environmental protection from a particular piece of legislation, based on the expertise of the OC, as well as advice for the most effective course of action. Thanks to the OC for this valuable tool!  Instructor and ESF attendees of the Advanced Occupancy Modeling workshop at Cornell. Back row, from left: Darryl MacKenzie, Alison Kocek, Wendy Leuenberger, Jonathan Cohen, Amanda Cheeseman, Maureen Durkin. Front row: Lisanne Petracca, Lilian Bonjorne de Almeida, Chee Pheng Low, Michelle Peach. Instructor and ESF attendees of the Advanced Occupancy Modeling workshop at Cornell. Back row, from left: Darryl MacKenzie, Alison Kocek, Wendy Leuenberger, Jonathan Cohen, Amanda Cheeseman, Maureen Durkin. Front row: Lisanne Petracca, Lilian Bonjorne de Almeida, Chee Pheng Low, Michelle Peach. One of the central problems in wildlife ecology and conservation is understanding the factors that affect the distribution of organisms in space and time. Distribution models often are used to study habitat relationships, interactions between species, and response to natural and human-induced environmental change. Surveys intended to document the presence of species at particular locations are usually biased by imperfect detection of organisms. This bias can be corrected through the use of Occupancy Modeling. Members of the Cohen, Frair, and Parry labs at ESF recently attended basic and advanced workshops in Occupancy Modeling hosted by the Cornell Department of Natural Resources. The workshops were given by Darryl Mackenzie, lead author of "Occupancy Modeling: Inferring Patterns and Dynamics of Species Occurrence." Participants gained practice with static and dynamic models, correlated detection and multi-scale models, multi-state models, and multi-species models. We look forward to applying these important tools in our own work! Nearly 10 years ago, I spent my first field season working with piping plovers on an small island in Massachusetts. When I was dropped off on the island, I was left with nothing but a binder that was named something like “Monitoring Protocols for Piping Plovers in Massachusetts,” which was written by Scott Melvin. Coming from Ohio, I didn’t even know what a piping plover was, let alone how to find a nest… I read the binder front to back on my first night, then went out to look.

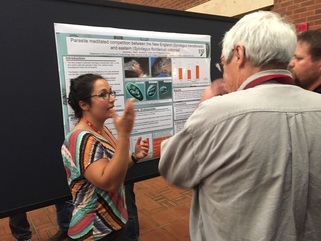

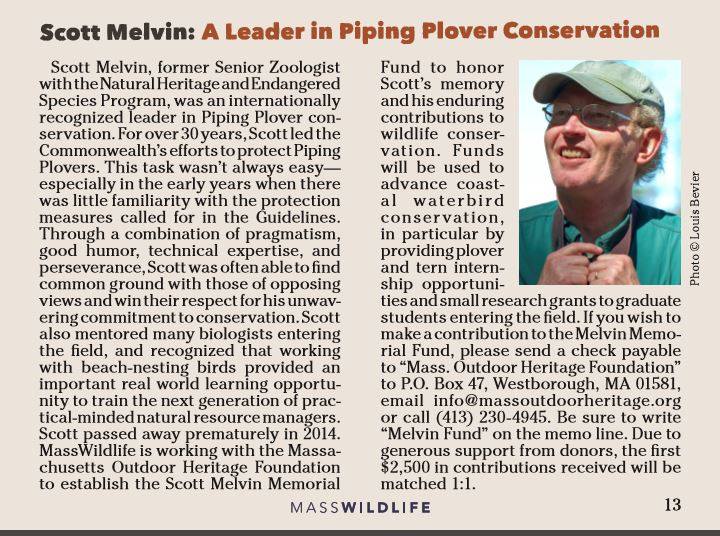

Oh man, did I totally stink at finding nests… I found most of them at 4 eggs, and one of them I didn’t find at all, I just discovered a brood of chicks running around on the beach one day. I referenced that binder constantly throughout that first field season, trying to decipher different calls and behaviors, trying to figure out what might be eating nests and what might be taking chicks… I was out there alone and I had no idea what I was doing, but I had that binder to guide me. Before I knew him, “Scott Melvin” became the voice in my head telling me what to do, where to look, and what the birds were doing. If you read the manual carefully, you will find hints of Scott’s sense of humor. There’s a section where he tells the bird monitor all of the equipment that they will need to take out into the field with them and buried inside that advice he offers that you might want to take along a Sherpa to carry everything. These little tidbits always made me chuckle at my situation. That fall, I had the chance to meet Scott, and I was tremendously humbled by how dedicated he was to the conservation of this species, and I was immediately inspired to dedicate myself to a species in the same manner. At the time, however, I had no idea that it would be piping plovers too. Eventually, Scott became a member of my Master’s committee, providing direct guidance towards my research of piping plovers. Today, he continues to be a voice in my head as my Ph.D. work focuses on piping plover conservation. Scott Melvin has touched the lives of many wildlife managers and wildlife biologists in a similar way, and he will continue to do so through the establishment of the Melvin Memorial Fund. The Melvin Memorial Fund will honor Scott’s memory and continue his legacy of the conservation of piping plovers. Please consider making a donation in honor of this conservation hero. Send a check payable to: Mass. Outdoor Heritage Foundation, P.O. Box 47, Westborough, MA and be sure to write “Melvin Fund” on the memo line. - Michelle Stantial  Dr. Cohen and Melissa celebrate the completion of her Master's degree in December. Dr. Cohen and Melissa celebrate the completion of her Master's degree in December. After a busy 2016 and an impressive three years, we are getting ready to bid a fond farewell to recent M.S. Melissa Althouse. Melissa went into the summer with her first peer-reviewed paper accepted into the journal Waterbirds. She then spent 12 weeks in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Directorate Resource Assistant Fellows Program, where she analyzed and summarized opportunities for conservation and migration of saltmarsh throughout Southern New England. On November 28, Melissa did a fantastic job defending her M.S. thesis, "Behavioral and Demographic Effects of Human Disturbance to Staging Roseate Terns (Sterna dougallii) in the Cape Cod National Seashore". The majority of the northwest Atlantic population of federally-endangered roseate terns gathers for several weeks at Cape Cod, Massachusetts prior to their long fall migration to South America. Melissa found that mixed-species tern flocks that included roseates were much more likely to flush in response to human pedestrians than to potential competitor species, even gulls which steal fish from terns that are attempting to feed their young. She also found that terns at less-disturbed sites tended to spend more time in flight and less in resting and related behaviors than terns at more-disturbed sites. She provided the seashore with much-needed guidelines for setback distances for human activity around tern flocks. Melissa's summer fellowship paid off, as she was offered a permanent position with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service after graduation. Melissa will be a Wildlife Biologist at Erie Natonal Wildlife Refuge in Pennsylvania. It has been fun having Melissa in our lab, and wish her the best for the next phase of her career!  Maureen presents her M.S. capstone seminar. Maureen presents her M.S. capstone seminar. As the Fall semester came to a close, the Cohen lab celebrated the successful defense of Maureen Durkin's M.S. Thesis, "Impacts of Anthropogenic Disturbance on Breeding Snowy Plovers (Charadrius nivosus) in the Florida Panhandle." Maureen's thesis work, spanning 120 miles of Florida coastline, compared behavioral and demographic responses of breeding snowy plovers to potential disturbance sources among several sites with varying amounts of recreational use. She found that birds at lower disturbance sites tended to react to humans at longer distances than birds at higher disturbance sites, and that humans evoked responses from further away than natural predators and competitors but that snowy plovers were most sensitive to dogs. Much of the current protection effort is focused on nests, but Maureen showed that plovers with broods were highly sensitive to potential disturbance. Although there was not a clear link between behavioral response to disturbance and reproductive success, she found that proximity to roadways influenced nest survival. Maureen is continuing on for her Ph.D. at SUNY-ESF, where she is focused on estimating wildlife road mortality and understanding population limiting factors for snowy plovers in Florida. Congratulations, Maureen! The Cohen Lab blog has been on a long hiatus as students became busy with their field seasons, and as I became focused on preparing my tenure dossier. But now it is turned in, and over the last few months it became clear to me what a tribute the dossier is to my excellent grad students and post doc, who have been tireless in their dedication to wildlife conservation and endlessly productive. A highlight of my job has always been my travels to visit their projects or accompany them to conferences. With that I offer my own tribute to my lab, through an account of our activities since the last blog post, in February. -- Jonathan Cohen “Field biologists are, on the whole, a guild of extraordinary people—smart, passionate, patient, congenial, and physically as well as intellectually tough.” – David Quammen, The Reluctant Mr Darwin  Michelle places a radio transmitter on a piping plover, assisted by fellow Ph.D. student Alison Kocek. Radio-tracking these threatened birds will allow Michelle to better understand how habitat changes and predators affect their population. She has documented interesting, unexpected movements within single breeding seasons. Michelle places a radio transmitter on a piping plover, assisted by fellow Ph.D. student Alison Kocek. Radio-tracking these threatened birds will allow Michelle to better understand how habitat changes and predators affect their population. She has documented interesting, unexpected movements within single breeding seasons. May 25 to 29: Cape May, NJ Alison Kocek accompanied me to visit Michelle Stantial in southern New Jersey. Michelle's study species is the piping plover, a threatened shorebird that has climbed from low numbers along much of the Atlantic Coast thanks to protections from human disturbance and predators. In New Jersey, however, the species is still not increasing despite intensive management efforts, and Michelle is working to understand why. She and her crew must cover an 80-mile long study area each week, because piping plovers nest in a few widely-separated locations in the state. On a given day her team may be banding birds, hiking for miles to look  Michelle inspects a recently-raised telemetry tower with her field assistant Rebeca, as Alison sets up a guy wire. These stations will remotely log the locations and movements of piping plovers, providing important information on habitat use and travel distances. Michelle inspects a recently-raised telemetry tower with her field assistant Rebeca, as Alison sets up a guy wire. These stations will remotely log the locations and movements of piping plovers, providing important information on habitat use and travel distances. for banded plovers or to count predator tracks, recording the foraging behavior of piping plover chicks, and building and setting up nest cameras and radio telemetry towers. This summer, Michelle instituted an internship program to train college students in piping plover research and conservation. She also found herself unexpectedly short-staffed, just before our arrival. Luckily we were able to give her a hand during our visit, and as the summer went on the Cohen lab rallied together as Master's student Justin Droke and post-doc Abby Darrah spent several weeks in New Jersey to assist Michelle. In what little free time she had during the field season, Michelle  Alison, Michelle, and Dr. Cohen finish placing a radio-tag on a piping plover female Alison, Michelle, and Dr. Cohen finish placing a radio-tag on a piping plover female helped to spearhead a collaborative effort among state and federal agencies to develop a coastwide standardized data collection system and monitoring database for piping plovers. While still in the field, she also wrote a lead-authored manuscript in cooperation with scientists from another University. It has been fun to see her emerge as a leader in the conservation of a species that I spent much of my career working on!  Maureen places an extremely tiny radio-tag on a snowy plover chick. This technique has helped her to identify the cause of mortality for many of these vulnerable young birds. Maureen places an extremely tiny radio-tag on a snowy plover chick. This technique has helped her to identify the cause of mortality for many of these vulnerable young birds. June 9 to 17: Gulf Islands National Seashore, FL Ph.D. student Maureen Durkin and her crew drive at a crawling 10 mph along 14 miles of road nearly every day for five months, recording roadkills of the imperiled snowy plover, least tern, and many other wildlife species at Gulf Islands National Seashore in coastal Florida. Maureen is studying the factors affecting reproductive success and population growth of snowy plovers, which are considered threatened in Florida, at a site where they are struggling to persist. In an already difficult environment, the threat of being run over on the paved road that runs the length the site creates an especial challenge for nesting birds and their chicks. Maureen is working with park officials to test strategies for conservation, including  Dr. Cohen and Maureen work with her field crew to band snowy plovers. Each day the team carefully searches miles of habitat for the banded birds, to learn about survival, movements, and reproductive success. Dr. Cohen and Maureen work with her field crew to band snowy plovers. Each day the team carefully searches miles of habitat for the banded birds, to learn about survival, movements, and reproductive success. vehicle speed reduction, so that managers can better protect the species. In addition to surveying the road, her crew painstakingly zigzags on foot for miles each day among the dunes and vegetated beach areas in search of camouflaged nests and young of the snowy plover. Along the way, they stop to band nesting adults, or adults with their chicks, a crucial technique for accurately determining productivity. They also record any previously-banded birds that they encounter. For several days in June I joined her team as they hit the beach at daybreak to avoid nest-searching in the worst of the sun’s glare, pressing on into the increasingly oppressive heat of  A stretch of road at Gulf Islands, which runs through miles of habitat including sensitive bird-nesting areas. Maureen and her team drive the road through the Fort Pickens and Santa Rosa Units of the Seashore each day to document wildlife road mortality. A stretch of road at Gulf Islands, which runs through miles of habitat including sensitive bird-nesting areas. Maureen and her team drive the road through the Fort Pickens and Santa Rosa Units of the Seashore each day to document wildlife road mortality. early afternoon. When the daily searching and monitoring surveys are done, Maureen and her team deploy and maintain cameras that record predators at snowy plover nests, and radio-track chicks to discover possible mortality sources. In her off hours during this past field season, she devoted herself to assisting other organizations with snowy plover field research, and grant writing to help build conservation programs for birds on the Gulf Coast and new projects for our lab. Maureen has fast become one of the most sought-after experts in Florida beach-nesting birds!  Sam describes her study, "Parasite meditated competition between the New England and eastern cottontail," at the American Society of Mammalogists conference. Sam describes her study, "Parasite meditated competition between the New England and eastern cottontail," at the American Society of Mammalogists conference. June 25 to 29: ASM in Minneapolis Ph.D. student Amanda Cheeseman and M.S. student Samantha Mello spend their days in the woods of the lower Hudson Valley of New York, where they study the elusive New England cottontail. The only cottontail rabbit native to eastern New York and New England, this once widespread species has dwindled to low numbers in a few remnant strongholds. The decline has been spurred by loss of young forest and shrubland, shifting predator communities, and competition from the non-native eastern cottontail which uses similar habitat. I met the two grad  Amanda, Dr. Cohen, and Sam at the ASM conference closing banquet. The conference included 5 days of presentations with topics ranging from the evolutionary history of rodents and bats to the spread of coyotes in modern-day New York City. Amanda and Sam were among the very few researchers at ASM focused on lagomorphs, which are rabbits and their kin. Amanda, Dr. Cohen, and Sam at the ASM conference closing banquet. The conference included 5 days of presentations with topics ranging from the evolutionary history of rodents and bats to the spread of coyotes in modern-day New York City. Amanda and Sam were among the very few researchers at ASM focused on lagomorphs, which are rabbits and their kin. students in Minneapolis for the American Society of Mammalogists conference in late June. At this meeting, over 200 of North America's leading experts in the evolution, ecology, and conservation of mammals gather each year to share their research. In Minneapolis, Sam gave her first major poster presentation, focused on parasites of the rabbits. Amanda gave a talk comparing habitat preferences of the two cottontail species. Her study will help wildlife managers determine how to plan forest restoration to promote New England cottontail populations without encouraging eastern cottontails. Year-round for three solid years, Amanda and her field crew have worked from morning to well after dark capturing and  Unexpected companion: a strangely tame ruffed grouse follows Amanda around her field site one day. Unexpected companion: a strangely tame ruffed grouse follows Amanda around her field site one day. radio-collaring rabbits, tracking them to learn about their daytime and evening habitat use and their survival rates, and measuring vegetation to characterize the habitat. In order to estimate the number of ticks in the rabbits' environment, Samantha drags a white cloth through a kilometer or more of tangled vegetation several days per week. These parasites are a potential health concern for the rabbits. When not she is not hauling sledfuls of heavy traps up a mountainside in snowshoes or pushing through miles of thorns and poison ivy to check traps or track rabbits, Amanda takes time during the field season to write manuscripts and grants, and to conduct outreach with local conservation and landowner groups. She works hard to try and promote sound management for New England cottontails and other young forest wildlife, and the state wildlife agency often looks to her for advice when planning restoration projects.  Adam with his poster on factors affecting site use by American black ducks and mallards in the Finger Lakes of New York in winter. Adam and Justin study the potential effects of mallards on winter and spring habitat use and behavior of American black ducks. Justin uses satellite tracking to compare migration timing of the two species. Their results will help waterfowl managers develop strategies to benefit the black duck in a landscape now dominated by mallards. Adam with his poster on factors affecting site use by American black ducks and mallards in the Finger Lakes of New York in winter. Adam and Justin study the potential effects of mallards on winter and spring habitat use and behavior of American black ducks. Justin uses satellite tracking to compare migration timing of the two species. Their results will help waterfowl managers develop strategies to benefit the black duck in a landscape now dominated by mallards. August 16 to 20: NAOC in Washington, DC In Mid-August much of the Cohen Lab attended The North American Ornithology Conference, where over 2,000 scientists from across the continent convene once every 4 years to present their work on all aspects of bird biology and conservation. I had the pleasure of accompanying seven of my students, my post-doc Abby, and my collaborator Dr. Michael Schummer with whom I co-advise two students. M.S. students Justin Droke and Adam Bleau presented posters on winter and migration interactions between mallards, which are not native to the northeastern US, and American black ducks, a species that has seen a steep population decrease in the last half-century.  Alison talks about the unexpected behavioral flexibility in nest site choice by saltmarsh sparrows she found in data collected across the species' range by a multi-University, multi-agency consortium. Alison talks about the unexpected behavioral flexibility in nest site choice by saltmarsh sparrows she found in data collected across the species' range by a multi-University, multi-agency consortium. Fresh out of their field seasons, Michelle Stantial presented a poster on her work on fox distributions in piping plover habitat, and Alison Kocek gave a talk on behavioral plasticity in choice of nesting vegetation by critically declining sparrows in the salt marshes of New York City. Master's student Melissa Althouse gave a talk on buffer distances to prevent human disturbance to endangered roseate terns at Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Melissa spent two summers following these birds throughout Cape Cod National Seashore to obtain information on the reaction of tern flocks to recreational activity. Her first paper was  The Cohen lab and collaborator at NAOC. Back row from left: Justin Droke, Adam Bleau, Dr. Michael Schummer, Dr. Cohen, Melissa Althouse, Michelle Peach. Front row from left: Michelle Stantial, Alison Kocek, Abby Darrah The Cohen lab and collaborator at NAOC. Back row from left: Justin Droke, Adam Bleau, Dr. Michael Schummer, Dr. Cohen, Melissa Althouse, Michelle Peach. Front row from left: Michelle Stantial, Alison Kocek, Abby Darrah accepted by the journal Waterbirds this summer. Post-doc Abby Darrah spoke on her quantitative modeling efforts to evaluate the costs and benefits of nest exclosures for piping plovers. Ph.D. student Michelle Peach studies how protected lands and climate affect changes in the distribution of birds at the landscape scale over long time periods. Her NAOC presentation on occupancy modeling using Breeding Bird Atlas data earned her a prestigious Cooper Ornithological Society Best Student Paper Award!  Alison begins her Master's capstone seminar. Alison begins her Master's capstone seminar. September 28: Alison defends! As the summer winds down, the members of the Cohen lab do not let up. September saw the impressive performance of Alison Kocek in defending her Master’s thesis on factors affecting presence and nesting success of saltmarsh sparrows and seaside sparrows in the highly urbanized and fragmented salt marshes of New York City. Alison became a Ph.D. student after working for two years on  Seaside sparrows (above) and saltmarsh sparrows (below) rely 100% on salt marshes. Seaside sparrows nest in the lower elevation part of the marsh but high in the marsh grass. Saltmarsh sparrows nest at higher elevation parts of the marsh, but lower to the ground. They are therefore vulnerable to losing their nests during the highest tides of the month. Sea level rise is expected to increase the rates of nest flooding, threatening the continued existence of the species. Seaside sparrows (above) and saltmarsh sparrows (below) rely 100% on salt marshes. Seaside sparrows nest in the lower elevation part of the marsh but high in the marsh grass. Saltmarsh sparrows nest at higher elevation parts of the marsh, but lower to the ground. They are therefore vulnerable to losing their nests during the highest tides of the month. Sea level rise is expected to increase the rates of nest flooding, threatening the continued existence of the species. her Master’s, on the promise that she would complete her M.S. program along the way. She has spent five years traveling among remnant salt marshes in Staten Island, Brooklyn, Queens, and Naussau County. From dawn until mid-afternoon, she and her field assistants criss-cross the eroding terrain of the marshes, searching for tiny nests hidden within the marsh grass, conducting banding operations to study survival and reproductive success, and measuring habitat characteristics. Saltmarsh sparrows face a dire threat in the form of habitat loss, as many salt marshes have been destroyed or degraded by human activity over the last century and what remains is flooded more and more each year due to sea level rise, causing frequent nest mortality. Alison’s thesis looked at the effects of vegetation, disturbance, and prey abundance on presence and nest success of the two sparrow species, in order to provide guidance for habitat restoration. With her Master's behind her, she is now diving fully into her Ph.D. dissertation work on phenotypic plasticity and factors affecting nesting density. Congratulations, Alison! Epilogue: Looking Forward

In my years as an assistant professor, my good fortune in the people who came to work with me never appeared to end. They are indomitable field biologists, avid conservationists, prolific writers, and globe-traveling ambassadors for their projects, their lab, and their school. They have supported each other and me in ways I hope I have repaid. So thanks to all of you, and I look forward to what the next six years will bring!  Ph.D. student Michelle Stantial scans a tropical beach for wintering piping plovers Ph.D. student Michelle Stantial scans a tropical beach for wintering piping plovers Every five years since 1991, the USGS has coordinated the International Wintering Piping Plover Census. In 2001, just 35 piping plovers were reported in the Bahamas, although there was little effort to survey the islands that winter. In 2006, a total of 417 piping plovers were found in the Bahamas on the winter census, an increase that was attributed to a more thorough survey effort. In 2011, the USGS, USFWS, National Audubon Society, Canadian Wildlife Service, Bird Studies Canada, Bahamas National Trust and several other organizations partnered together for an unprecedented effort to count wintering piping plovers. During this survey, a total of 1066 piping plovers were observed, exposing the Bahamas as one of the most important wintering locations for piping plovers. When I first began working with piping plovers, the 2006 census had just been completed, pointing towards the Bahamas as the newest place to explore for wintering piping plovers. When the 2011 census came around, there was great excitement from my friends and colleagues who would be heading to the Bahamas, making new discoveries of important piping plover wintering locations. Five years ago, I couldn’t have imagined that I’d still be working with piping plovers today, let alone participating in the 2016 International Wintering Piping Plover Census and heading for the Bahamas. This January, I traveled to Abaco with Todd Pover, Stephanie Egger, and Emily Heiser of the Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey, Brenden Toote from the College of the Bahamas, and Pam Prichard to begin our work. We counted a total of 172 piping plovers on Abaco, including one banded piping plover from Jamestown, North Dakota! After a week of surveys on Abaco, I traveled with Todd, Stephanie and Emily to Eleuthera where we counted a total of 82 piping plovers. Now that the survey effort across the wintering range has revealed the Bahamas as an important wintering area, especially for Atlantic coast breeders, there are many opportunities to learn more about the wintering ecology of piping plovers. Specifically, we can now work to identify what types of habitats are favorable for roosting and foraging, allowing continued protection into the wintering grounds. I would like to offer a very big “Thank You,” to Todd Pover for his tireless efforts to coordinate the census on both Abaco and Eleuthera and for inviting me to participate. It was truly a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. - Michelle Stantial  The Saltmarsh Habitat & Avian Research Program (SHARP) crew, 2015 The Saltmarsh Habitat & Avian Research Program (SHARP) crew, 2015 Dr. Cohen and Ph. D. student Alison Kocek traveled to the University of Connecticut in mid-December to attend the 2015 Saltmarsh Habitat & Avian Research Program (SHARP) Working Group Meeting. SHARP is a group of academic, governmental, and non-profit collaborators that formed in 2011 to research and monitor tidal marsh endemic birds and the salt marsh habitat that supports them along the northeastern coast of the United States. Tidal marshes are unique habitats that provide ecosystem services such as water quality improvement, flood control and moderation of storm surges during weather events, and sequestration of carbon dioxide. They also provide habitat for migratory birds, fish, and wildlife, including several endemic species. However, between the 1950’s and 1970’s, nearly 50% of the tidal marshes along the United States’ Atlantic coast were lost due to human activity. SHARP researchers strive to inform management actions across the northeast United States for the long-term conservation of tidal marsh birds and the ecosystem that supports them. SHARP also provides a consistent platform for monitoring the health of North America’s tidal-marsh bird communities and the marshes they inhabit in the face of sea-level rise and upland development. At the 2015 Working Group Meeting, SHARP members discussed current research projects and developed new ideas for future research and conservation strategies for tidal marshes and their wildlife. Members discussed a Species Status Assessment for the saltmarsh sparrow (Ammodramus caudacutus) that will be presented to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service in early 2016 as part of a proposal for listing the species under the Endangered Species Act. The saltmarsh sparrow is an imperiled tidal marsh obligate breeding sparrow. Conservation of habitat for this species will protect the entire suite of typical tidal marsh inhabitants which is the overarching goal of SHARP. |

Categories

All

Archives

July 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed